Chugging down the memory lane

Text : Preetha Banerjee

I was 9 or 10 when I was accompanying my parents on our biennial trip to Shantiniketan or ‘the land of the red soil’ as Rabindranath Tagore had described it. For Bengalis, the trip often doubles as a cultural pilgrimage with Visva Bharti, the university that Tagore built, as the Mecca.

I remember being less excited about visiting Shantiniketan than my parents were but that afternoon, as my father began running to catch the train, with a suitcase in one hand and me in the other trailing behind, and the whole atmosphere of the platform—the uncrowded magazine stalls, coolies in red tunics, people sitting on their luggage—whizzing past me, I sensed excitement rising in me like bubbles in a drink.

It was a warm May afternoon. Silence had won over chatter in our coach as the passengers had settled in their seats. Just that one three-year-old child cried out every time it hurt itself while wobbling back and forth between its parents. A woman fanning her face with the end of her ‘pallu’, the teenage boy reluctantly staring at the same page of his book for the last hour—all these characters, who'd be my companions on the journey of close to three hours, had grown too familiar to be explored further. Soon, it was the fleeting landscapes from my rusty train that window caught my attention.

Long after we had left behind our city of black-yellow taxis and sky scrapers, the train meandered through the villages of Bengal, splicing the landscape into two.

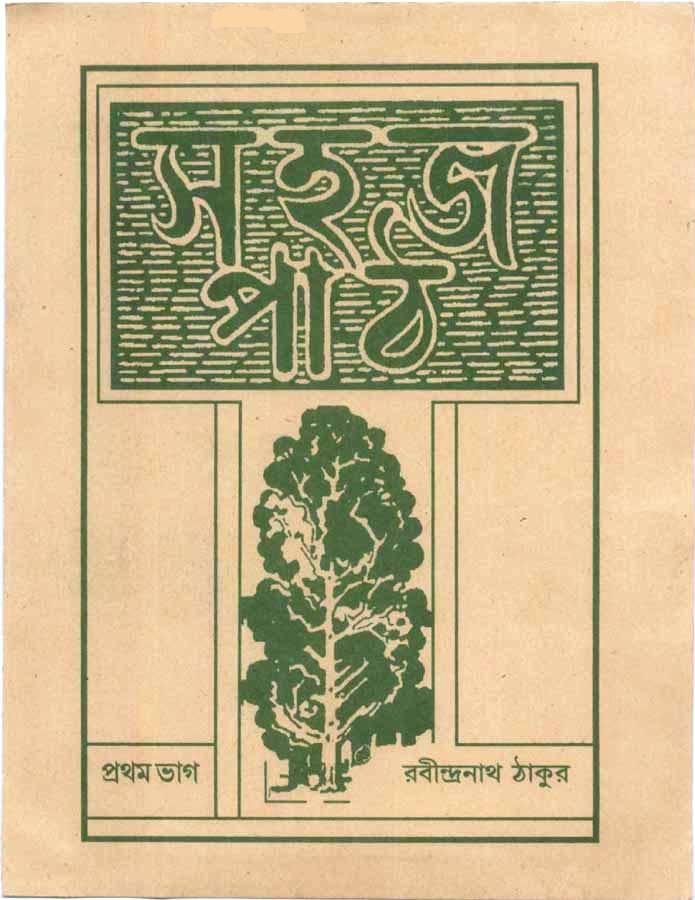

A cover of Sahaj Path, by Rabindranath Tagore. Illustrated by Nandlal Bose.

Organized patches in varying shades of green with a small stretch of water towards the edge, were the mise-en-scene. It felt like modernist Nandalal Bose’s black-and-white linocut illustrations in Tagore's Sahaj Path were coming alive.

The book, filled with the great poet's short rhymes had not too long ago helped me memorize my first Bengali alphabets. As a city kid, it was through Bose's silhouettes of village skylines that I'd imagine Bengal's villages in vivid colours. These were now right in front of me, as I looked out my train window, a secret ringside seat to my flights of imagination.

An old tree was stretching its green branches to touch the calm water of the pond.

Lino cut illustration by Nandalal Bose for Sahaj Path 1930

Tied to it, a cow was standing indifferent to the young boy chasing a rubber tyre with a thin wooden stick.

This scene became an extension of those paintings. It had also reminded me of the stereotypical drawings of rural scenes that almost all kids did when they learnt drawing in school.

As I think back to that now, a few lines from a Tagore poem, 'Sonar Tori' come to mind encapsulating what I saw:

Translation:

I sit alone on a small farmland,

The bent waters all around keep playing their game,

On the opposite bank, I see

Smoky shadows of the trees

And the village enshrouded by clouds

It is dawn

And on the small farmland on this side,

I sit alone.

That day, the same crooked creek that Tagore had described, seemed more beautiful to my young eyes, than I had imagined while reading those lines. It was urging me to pull the chain to stop the train, take out a blank canvas and start painting. I wouldn’t have minded the chaos this disruption would cause.

Suddenly, to my quiet surprise, the train which was still about fifty minutes away from Bolpur, the gateway to Shantiniketan, slowed to a stop. My mother read the surprise on my face.

"It stops here for 15 minutes almost every time," she told me.

The landscape, in that last couple of minutes, had turned arid. Where we stopped, the ochre of the endless stretches of land on either side seemed to be pouring into our train compartment. In its vast silence, it commanded everyone to stop making any noise.

The heat of the late-day sun was starting to overpower everyone on board when suddenly, strains of an ektara broke the silence like a spell of awaited rain. It was a baul fakir, with madness in his hair and worldliness in his unrestrained voice, who'd gotten on the train. His large smile made the rest of his body look frailer than it was. He burst out into song:“Ekbar dhorte pele moner manush chhere jete aar diyo na” (If you ever meet your soulmate, don’t let him go).

As the train blew its long horn, and started chugging back to life, the fakir's soul-searing songs carried us into Shantiniketan, his hometown.

Till today, when I'm bogged down by the small struggles of daily life, his contented face floats back in my mind. Even now, the smell of rust never fails to take me back to the rattling metal windows of that train to Shantiniketan, and the images and epiphanies that they had opened up, even before I knew what I was processing.

Preetha Banerjee is a social media executive who denounces the very existence of such platforms. In her imagination, she is constantly drifting among galaxies.